Americans breathlessly and nervously await the ultimate fate of the “One Big Beautiful Bill” and its impact on the economy, the community, and our personal bank accounts. As soon as one reads an article about what the bill contains, it changes, frustrating many who do not understand how the process works. Additionally, the bill currently sits at 1,116 pages of tax, spending and social policy all written in mind-numbing legalese that puts the reader to sleep faster than Tylenol PM.

A poll by the Pew Research Center last year revealed that one of the top frustrations of American taxpayers was the complexity of the federal tax system. In fact, this is one issue on which nearly everyone agrees, regardless of party affiliation. Another poll from the Tax Foundation published in December 2024 found that 88% of Americans think the federal tax code needs reform. With the Internal Revenue Code weighing in at over 4,000 pages, it is hard to argue otherwise.

Individual income taxes accounted for 49% of total federal revenue in 2024. Payroll taxes for social security and Medicare, also levied on individual taxpayers, is the second largest source of federal revenue. In other words, we the people have skin in the game. A lot of it. Yet tax literacy is not taught in our standard K through 12 curriculums, and a majority of respondents in the Tax Foundation poll were either unaware of or unsure of basic tax concepts. In fact, only 2% of respondents exhibited “proficient” tax literacy.

In this article, we will attempt to fill in some of the blanks so you can be among the 2%. Additionally, we will briefly discuss the tax law process so first we can understand where we are in the timeline for the “One Big Beautiful Bill” and second so that in any discussion around tax reform, we have a better handle on what that process would entail, and why it is so difficult to achieve.

First, a look at a few of the Tax Foundation’s tax literacy poll questions.

Question – To the best of your knowledge, what tax rate applies to the top U.S. federal income tax bracket: 22%, 32%, 37% or 43%?

Of the 59% of respondents that believe the federal income tax rates are too high, and the 65% who believe the U.S. Tax Code is unfair, only 35% were able to identify the correct top income tax rate. The correct answer is 37%

Question – To the best of your knowledge, do you think the average U.S. federal income tax rate is 3%-4%, 13%-14%, or 25-26%?

This question is a bit confusing and can have two answers. If the question is meant to address tax rates, we first must understand if they are asking about marginal rates or effective rates.

Marginal tax rate is the tax rate applied to the last dollar of income earned. In other words, the top tax rate an individual pays, or the “tax bracket” they land in when considering their total income. The marginal rates are applied based on income levels for different types of filers and are the 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32% and 37% seen on the tax tables.

Effective tax rate is the average rate at which your total income is taxed. The federal tax system is progressive, meaning that as you earn more, your tax rate increases, but it does not increase for every dollar earned. Everyone enjoys the same benefits of the lower brackets on their first dollars earned and only find themselves in the higher brackets when they break the thresholds of earnings.

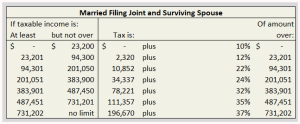

Example: Jack and Diane, a married couple, earned $100,000 of taxable income in 2024.

Assuming no credits or capital gains, their income tax would be $12,106 based on the above chart. Their marginal rate, according to the published tax tables, is 22%; however, their effective tax rate is only 12.1%. Why? Only $5,700 of their taxable income is taxed at the marginal rate. The remaining $94,30 is taxed at the lower rates; specifically, $23,200 is taxed at 10% and $71,100 is taxed at 12%

So, to the question above, we would want to know which average rate they are asking for. Luckily, in this case, the correct answer is the same: 13%-14% for both.

Question – To the best of your knowledge, how much do you think the top 1% of taxpayers, by income, account for in terms of share of total federal income taxes paid: 1%, 12%, 42% or 64%?

58% of respondents believe the federal tax burden should shift by having high earners pay more, but only 18% of those were able to correctly answer this question. Of the 65% who believe the U.S. Tax Code is unfair, only 21% were able to correctly answer this question.

The correct answer is 42% despite earning approximately 20% of total adjusted gross income.

Question – Suppose you are being taxed at a rate of 10% on $10,000 of income, which do you think is more valuable to you: a $1,000 income tax deduction or a $1,000 income tax credit, or do you think those are the same thing?

A credit is more valuable than a deduction. A deduction reduces the amount on which your tax is calculated, while a credit reduces your actual tax, or another way of looking at this is deduction is a reduction of a percentage of your tax, whereas a credit is a dollar-for-dollar reduction of your tax.

In this example, a $1,000 deduction would save you $100 in tax as follows: Taxable income of $10,000 – $1,000 deduction = $9,000 of taxable income x 10% tax rate = $9,000 net tax due.

A credit, however, would save you $1,000 in tax as follows: Taxable income of $10,000 x 10% tax rate = tax of $1,000 – $1,000 tax credit = $0 net tax due.

So how did you score on those questions? If you did not answer them all correctly, hopefully we were able to improve your understanding of these issues, at least.

Now that we all agree that understanding Tax Code is a challenge, how does the “One Big Beautiful Bill” become part of the code, and what steps would need to be taken to achieve tax reform at some point?

Per the U.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section VII, all bills for raising revenue are initiated in the U.S. House of Representatives. This, of course, includes tax law.

When a bill is initiated, it is referred to the Ways and Means Committee (The WMC), the oldest committee of the United States Congress. The WMC consists of 45 members, currently 26 Republicans and 19 Democrats, and is broken into subcommittees to address specific areas for which The WMC is responsible. The Subcommittee on Tax consists of 19 members, currently 11 Republicans and 8 Democrats.

The subcommittee meets and discusses various aspects of the proposed legislation. They often have hearings in which they call people to testify on certain items. They weigh the pros and cons and decide on what they want the bill to contain, and they write the first draft.

The process repeats until the entire WMC can come to a majority agreement on the bill and the revised draft is sent to the House floor. The process repeats for a third time for the entire House of Representatives. Elements of the bill are discussed and debated. Revisions are made until again a majority of the entire House can agree on the bill.

Once passed, the bill moves on to the Senate. The bill is passed to the Senate Finance Committee (SCF), which operates in a fashion similar to the House WMC. The bill is generally referred to the Taxation and IRS Oversight subcommittee, currently composed of 17 members: 9 Republicans and 8 Democrats. The subcommittee reviews, discusses, debates, revises and often entirely rewrite the bill in order to come to a majority agreement. The draft is then passed on to the entire SCF and the process repeats until the 14 Republicans and 13 Democrats (currently) can reach a majority agreement. The bill is then passed to the entire Senate, and the revision process repeats at that level until another majority agreement can be reached.

While in the Senate, a filibuster can delay a bill unless it qualifies as a budget reconciliation item. A filibuster is a tactic employed by the minority voters to delay and ultimately prevent legislation from passing by prolonging debate, introducing time consuming procedural motions or even talking endlessly until enough people agree to change their vote and revisit the issue, or enough people end the filibuster via cloture, which requires a three-fifths majority for the bill to pass, or 60 Senate votes, also known as a supermajority.

This delay tactic can be avoided by structuring the bill as a budget reconciliation item, exempting it from filibuster and expediting the process of passing the bill into law with a simple majority. To qualify for budget reconciliation, a revenue or tax bill must meet six requirements, the most relevant of which are it must produce a nonincidental change in revenues, it cannot change Social Security, and it cannot increase the deficit beyond 10 years. This is why we see so many tax laws with sunset provisions so as to not extend the effect beyond 10 years.

Since the Senate bill rarely, if ever, matches the House bill item for item, the bill is passed to a joint committee of House and Senate members where they try to reach a compromise both arms of the legislature can agree to. If they are able to accomplish this, the compromise version of the bill goes back to both the House and the Senate for approval. If majority votes are achieved in both Congressional chambers, the bill is passed on to the president to sign or veto.

If the president signs the bill, the bill becomes law and is codified into Tax Code. If the president vetoes the bill, Congress can still pass the bill with a two-thirds majority vote in each house, even without the president’s signature. This isn’t common though, having happened only 112 times in our nation’s history.

In summary, I think we can all agree the Tax Code is complicated and messy. The process for passing tax legislation is arduous, even for one bill. Now imagine the process of overhauling the entire Tax Code or creating an entirely reformed taxation model.

The “One Big Beautiful Bill” is currently in the Senate Finance Committee. They have released some of their proposed revisions, but the bill has not gone to a vote of the full Senate as yet. Even when it does, there are many more hurdles to jump before the race is over. The President was eager to have the bill on his desk before July 4th, but that is looking increasingly unlikely. As keen as Americans may be to know our collective tax fate, at least for the next several years, we have to wait until the final version of the bill is signed by the President before we will know for sure. As Tom Petty once said, the waiting is the hardest part.